Index:

- The political situation at the time of the treaty

- The Kurdish people divided into four states

- Our solution: the Democratic Nation

With this article we want to demonstrate the consequences of the Treaty of Lausanne 100 years after it was signed, particularly in our territory, the Middle East. As YPJ, we see the need to share these reflections because we believe that many of the threats from which we have to defend ourselves in the present-day stem from that time, when nation-states were established here. The struggle and resistance against the nation-states in our lands was the impetus for the elaboration of the proposal of Democratic Confederalism by our leader Abdullah Ocalan; his proposal is the basis of the revolution of which we are part.

What are the consequences of the advent of nation-states within our land? How do they fit into a territory which actually comprises of many different cultures and nations intersecting in a colorful mosaic? How are ethnic minorities or cultures other than that of the nation-state considered and treated here? What forms of resistance are practiced and what repression, violence and massacres are exercised toward those who resist? What alternatives, finally, have these resistances been able to put in place? To what extent can we find the answers to the needs of a humanity in crisis within the alternatives constructed here? For this, it is important to begin with an analysis of history.

The political situation at the time of the treaty

It is 1923. World War I ended five years ago with the dissolution of the multinational Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman, Russian, and German empires; nation-states are emerging as the only form of government in a Europe with strong colonial policies. On the one hand, Benito Mussolini has just become prime minister in Italy and Hitler is beginning to enter politics in Germany, while on the other hand, a few years earlier, the October Revolution in Russia kindled the hopes of the world’s working class. In Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, who would become the first president of the republic of Turkey in October of that year, is making his way into the Turkish National Assembly.

The beginning of the construction of the Turkish national identity

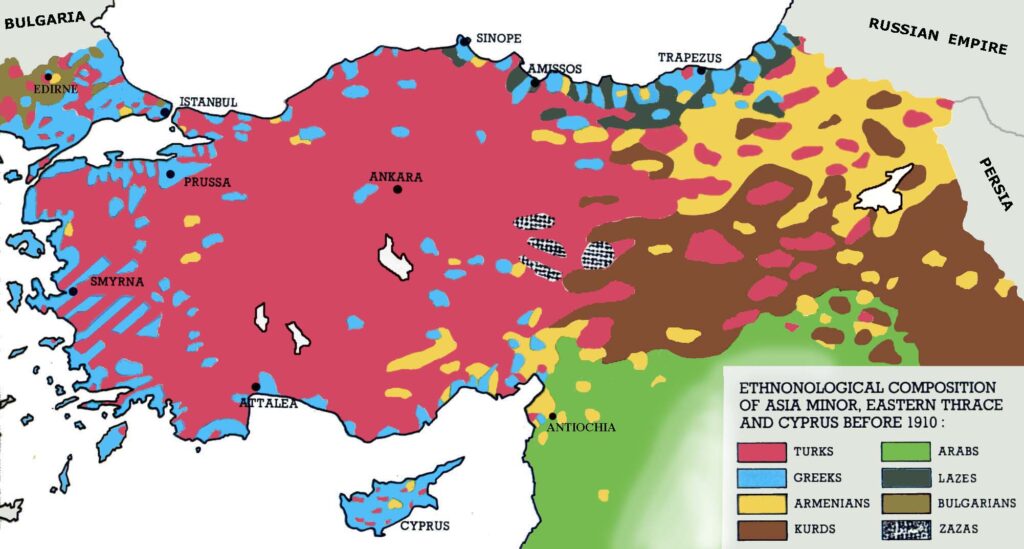

Turkish peoples originated in present-day Kazakhstan and belonged to the group known as the “Huns” moved to Anatolia in the 11th century AD. In 1910, peoples of Turkish ethnicity did not comprise the majority of the population of the territory of present-day Turkey. Azeri, Laz, Kurds, Circassians, Greeks, Armenians, Assyrians, and Jews were all present. In particular, the island of Cyprus, the coasts facing the Mediterranean and part of those facing the Caspian Sea, as well as some inland areas, were predominantly Greek, the southeast was predominantly Kurdish, and the northeast predominantly Armenian. The Ottoman Empire, while retaining profound authoritarian and undemocratic characteristics, did not have the nation-state approach whereby a state must be characterized by a single language, religion, ethnicity, and nation. Now the Ottoman Empire, among the losers of World War I, was about to be dissolved.

Turkish nationalist movements, led by the Young Turks to which Mustafa Kemal belonged, had the goal of building a nation-state like those in Europe. In the wake of this idea of an ethnically homogeneous territory, between 1915 and 1919 the Ottoman Empire carried out genocides against at least 3 different peoples: firstly, against the Armenian population, which resulted in the killing of 1.5 million people in deportations and beyond. To date, the Turkish state does not recognize these events as genocide. Right after that, a genocide against the Greek people (particularly toward – but not restricted to – the Greek-Pontic minority) resulted in between 289,000 and 750,000 casualties, while the genocide against the Syriac people resulted in the massacre of 275,000-750,000. These genocides were mainly carried out by the “Young Turks” group, of which Mustafa Kemal Ataturk was a member. This group was laying the groundwork for the establishment of the future Turkish republic. It is interesting how, although the motive according to many historians was more nationalist than religious, the first persecutions were carried out against non-Muslim groups.

This is probably because the Turkish nationality was not yet sufficiently defined to convincingly identify the “other” in a non-religious way. These actions resembled Nazi genocides in many ways; indeed, Hitler called Ataturk his master. It is logical that these genocides, as much as those that would happen in Europe a few years later, were connected to the birth of the nation-state: a form of territorial government that only accepts a single nationality within itself. That’s why, in order to lay the foundation for the construction of the Turkish nation-state, it was necessary at the very beginning to exterminate populations of different religion, culture, and ethnicity from the state one.

What happened just before the Treaty of Lausanne

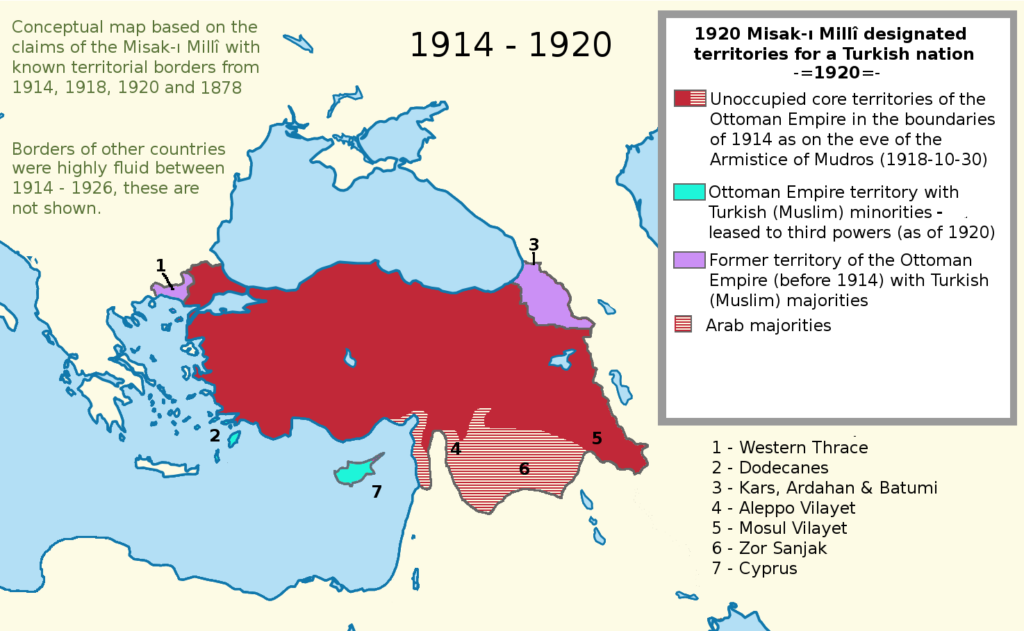

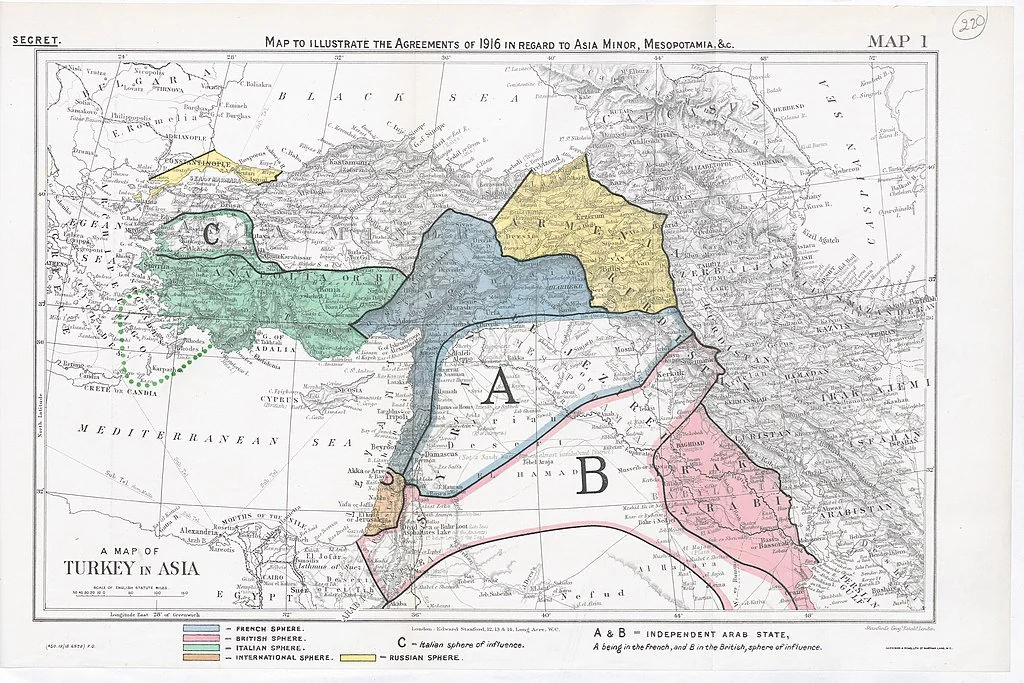

In 1916, the Sykes-Picot Agreement (also called the “Asia Minor Agreement”) laid the foundation for the colonial division of the Middle East, with the partitioning of our territory between the zones of influence of the French and British colonial powers, with no regard whatsoever for existing ethnic, linguistic, national, and religious differences. When the parliament of the Ottoman Empire met for the final time, on January 28th, 1920, they made an oath (or pact) called Misak-ı Millî, which (among other things) proposed the borders of the yet to exist Turkish state, to include Cyprus, the northern part of Syria, and into Iraq until Mosul. Even in the future the Turkish state would never be as big as described in Misak-ı Millî but, since then, Turkish nationalists have dreamt of achieving those borders.

Right after this, on August 10th, 1920, the Treaty of Sevres was signed between the victors of World War I, Germany, and the Ottoman Empire. In this agreement Turkey was divided into zones of influence and the possibility of the existence of a Kurdistan, a small area in the far southeast of present-day Turkey was floated. Articles 62-63-64 of this treaty contemplated the construction of a territory under Kurdish rule, assigned a multinational commission to define its boundaries, and obligated Turkey to submit to the decisions of this commission. In 1921, components of the Turkish National Assembly signed the Kars Agreement with the Soviet Union, defining the borders between Turkey and the republics of Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia. This enshrined in fact an alliance between the nascent Turkey and the Soviet Union, and this increased the bargaining strength of Turkey, which would soon declare that it did not recognize the Sevres Agreement, requiring another conference.

This conference began in November 1922 in Lausanne, Switzerland, and was attended by Britain (Lord Curzon chaired it), France (with a speech by Raymond Poincare), Italy (with a speech by Benito Mussolini), and the Turkish National Assembly. İsmet İnönü (one of the founders of Turkish State and the second president of Turkey, following Mustafa Kemal), representative of the Turkish national assembly, showed great stubbornness, to the point of refusing to sign the final agreement after 11 weeks of the congress, so that in February 1923 Lord Curzon abandoned the works, leaving them without an effective result. After that, Turkey made a new proposal and in March 1923 the conference re-opened. By July 24th, 1923, the Treaty of Lausanne was finally signed.

The Treaty of Lausanne

The signing of the Treaty of Lausanne opened the door to the creation of nation-states in the Middle East; in particular that of Turkey. Of course, there was no acknowledgment of us, the people living in the area, and specifically the historically Kurdish inhabited area (Kurdistan) was not recognized in any way. The end result was Kurdistan’s division into the states of Turkey, Iran, Iraq and Syria.

The treaty declared an amnesty for the events that occurred between 1914 and 1920 (such as the genocides against Armenians, Greeks and Assyrians) and in this way implicitly declared the expulsion and massacre of ethnic groups lawful. Interestingly, in January 1922, a treaty was ratified that authorized the deportation of the Greek (Christian) population from Turkish territory and simultaneously authorized the transfer of the Muslim population of Greece to Turkey. Ethnicities other than Turkish that were recognized in the treaty were Greek, Armenian, and Jewish. The treaty stated that religious minorities were not to be discriminated against. The Kurdish people, however, were not mentioned. Although it was explicitly stated that (art. 39) “[…] No restrictions shall be imposed on the free use by any Turkish national of any language in private intercourse, in commerce, religion, in the press, or in publications of any kind or at public meetings […]” these concessions in practice did not apply to Kurdish people.

Turkey’s borders were redrawn, and the external areas of influence within Turkish territory that were present in the Sevres Agreement were eliminated. The territory of Turkey was smaller than the one described in Misak-ı Millî, yet still Mustafa Kemal defined the Lausanne treaty as, “a diplomatic victory unheard of in the Ottoman history.” A Europe in which fascism was gaining ground gave Turkey the green light to complete the artificial construction of Turkish identity and get all those who did not match with this identity out of the way. In the agreement, not once was the word Kurdish or Kurdistan written (although the Kurds were one of the most populous ethnic groups in the area). In fact, not one reference was made to this thousands-of-years old people.

The Kurdish people divided into four states

With the Lausanne treaty the Kurdish people found themselves divided into 4 states (Turkey, Syria, Iraq, Iran). The other peoples present (Syriac, Armenian, Circassian, Laz, etc.) also found themselves divided and caged into state entities that did not and do not acknowledge their nationalities. In many cases families found themselves separated by a border, unable to rejoin again; some towns (such as Nuseybin/Qamishlo or Ceylanpinar/Serekaniye) found themselves cut in two by the new border.

Turkey

After the Treaty of Lausanne, the main goal of the Turkish government, based on the ideas of Mustafa Kemal, was to assimilate all cultures that were not Turkish. Ismet Iononu had this to say: “Our mission is to turn everyone who lives within Turkish borders into a Turk,” and one of the slogans of the newly formed republic was “how happy I am to be a Turk.” Specifically, this meant that within Turkish territory it was necessary to love Turkishness. Article 103 of the Turkish Penal Code provided for a penalty of six months to two years for anyone who publicly denigrates the Turkish nation, the Republic of Turkey, the Grand National Assembly of Turkey, the government of the Republic of Turkey, and the judicial organs of the state.

From here on, everything that was not Turkish would be turned Turkish or erased, in line with the most fascist interpretations of the idea of the nation-state. Everyone who wanted to enter the work or educational system required knowledge of the Turkish language. In 1980, the Kurdish language was banned in the public and private spheres: not only in public offices or in the streets, but also at home. Kurdish names and the words Kurdish and Kurdistan were banned. Clothing and traditions, including the important celebration of Newroz (new year at the spring equionox) were banned. Villages were burned and there was forced deportation of Kurdish populations to other parts of Turkey for the purpose of assimilation. Kurdish-inhabited areas were put under martial law. Arrests of Kurdish politicians, artists, and journalists continued unabated. The erasure of other identities went so far as to claim that Kurdish ethnicity did not exist and that Kurds were just “Turks of the mountains” and that the name was derived from the “kirt kurt” sound that shoes make when walking in the snow.

This is despite the fact that the Kurdish population is one of the oldest populations in the area (the Kurdish name is derived from kur-ti, meaning “coming from the high places” and has Sumerian origins) while the Turkish population, as described before, immigrated to the area only relatively recently. In the face of this discrimination, the resistance of the Kurdish people has continued. There have been heroic episodes and, in several cases, women have played an important role. The people rose up dozens of times. In many cases it was tribal leaders who led the uprisings as in the case of the Sheikh Sayid uprising in the Diyarbakir area, where 600 rioters were hanged, 500,000 people were deported and about 300,000 civilians were killed.

Another example is the rebellion in Dersim, a Kurdish city with a majority Alevite religion (a form of Islam that still retains many traces of ancient Zoroastrianism) that had not accepted central power since the time of the Ottoman Empire and was persecuted particularly for its faith. The repression that followed this uprising involved so much bloodshed that the Munzur River that runs through the city is said to have changed color to red (figures vary from 15,000 to 47,000 dead). Turkish soldiers repeatedly raped Kurdish women, so much so that thousands threw themselves off rocks in order not to end up in their hands.

Syria

If we look to the consequences of Lausanne in the Syrian Arab Republic, we can see that even if Syria takes its name from the Syriac ethnic group present in the area, it still calls itself Arab, proceeding to Arabize all the peoples in its territory. In Syria, the Kurdish people are mainly found in the area to the north, near the border with Turkey.

The Ba’ath government made the decision to establish an “Arab belt” in that area. It transferred some of the Arab population and forced the Kurdish population to emigrate while confiscating belongings. In Syria, citizenship was revoked from much of the Kurdish population in 1962. Those Kurds without citizenship could not enjoy the same rights to work and study as Arab citizens. The Syrian state distributed basic necessities at a low price to its citizens, including water and electricity: these benefits did not reach the stateless population. Participation in the school program was allowed but without receiving an actual diploma. It was impossible for stateless people to acquire land and housing. In Kurdish-majority areas, employment and educational opportunities were in any case reduced to a minimum, and the names of all offices, schools, etc. were converted to Arabic. In Syria, the case of the cinema in the town of Amude is famous. The cinema was full of 500 children when it caught fire: 283 lost their lives. The doors of the cinema were locked, and no one could open them. Despite this, the government did not carry out any investigation.

Iraq

In Iraq, the revocation of citizenship for Kurds took place in 1979, the same period as the persecution and deportation of Kurds belonging to the Feyli tribe from Iraqi territories. 200,000 Kurds belonging to this tribe were driven out of Iraqi territory between 1961 and 1970. In the Anfal massacre, carried out by the Iraqi Ba’ath government in southern Kurdistan, massive use was made of chemical weapons, so much so that according to local figures 182,000 people died, dozens of thousands were injured or disabled, and 220,781 families (1,021,758 people) were forced to leave their homes.

An important example was set by the resistance of Layla Qasim, a Kurdish student from south Kurdistan. Before being killed by the Ba’ath regime in Iraq she said, “Kill me, but be aware of the fact that by killing me thousands of Kurds will wake up from deep sleep.” There were dozens of massacres and deportations in the 4 parts of Kurdistan, and we refer to future readings for a more complete analysis.

Iran

In Iran, repression against Kurdish people included evictions, destruction of homes, economic neglect of Kurdish-inhabited areas, arbitrary arrests, and persecutions. In Iran there is the death penalty and, in many cases, Kurdish activists were hanged.

The role of the PKK

All these uprisings and rebellions once again show the resilience of the Kurdish people, their resistance to assimilation and their combativeness. So why then have these uprisings failed? One of the reasons is that due to the division of the Kurdish people between 4 states, their uprisings are fragmented. The divisions, whether between different tribes or dictated by state boundaries, meant that their struggles did not become one and for this reason one by one they were suppressed. Moreover, there was a lack of a strong leader who could carry forward a strong proposal. On this line, an important breakthrough happened with the founding of the PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party) in 1978 by Abdullah Ocalan and the beginning of its armed struggle in 1984.

For the first time, this was not a rebellion tied to a tribe or limited to one of the four states but was a broader revolution. Guerrilla warfare succeeded in giving strength and hope to an entire people. Repression, particularly by the Turkish state against this party, ranges from torture in prisons, to burning the villages of peasants who supported the revolutionaries, now to the use of poison gas and so on. In light of the oppressions carried out by states, in light of the history of our people, the people’s leader Abdullah Ocalan finally managed, through the democratic nation project, to propose a peace solution not based on state-building and which manages to preserve and respect the different ethnic and cultural identities present.

Our solution: Democratic Nation

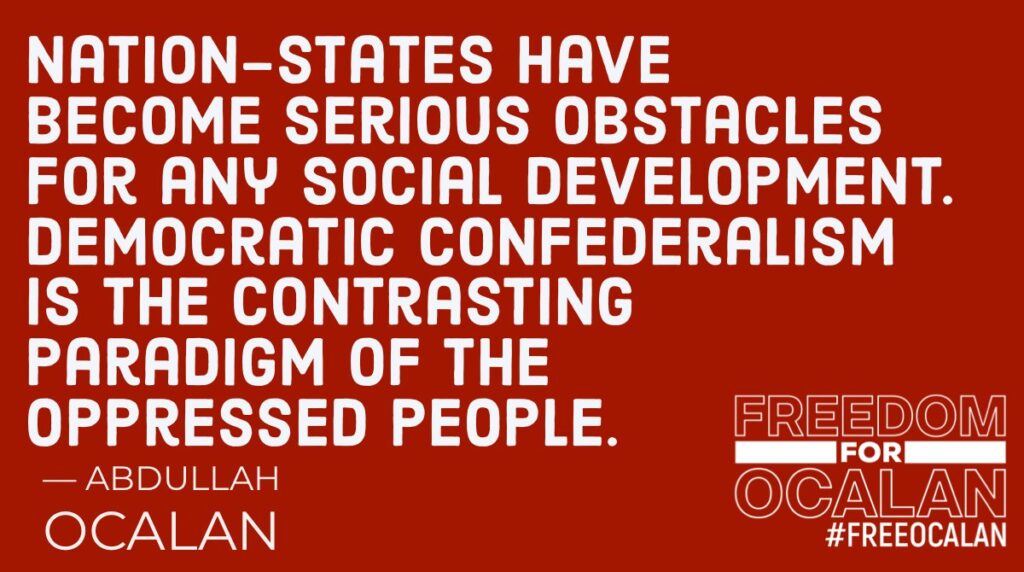

What we see here is that a form of power – the nation-state – that was not native to the Middle East has been imported to our territories. After one hundred years, the wars going on here evidence that nation-states, based on the ideology of one nation for one state, fail to bring peace to a territory where the peoples, ethnicities, and nations present are mixed into a colorful mosaic. In Turkey, Erdogan is still thinking about the Misak-ı Millî oath, and still declares that one day Mosul and Cyprus will be under his control, dreaming of the glory of the Ottoman empire. For this reason, Turkey is occupying Efrin, Serekaniye and Gire Spi. In those areas Turkey is carrying out demographic change with forced deportations and ethnic cleansing. These nation-states, whose borders and characteristics have been imposed on us, have built their identity on blood; on the physical and cultural extermination of the different peoples present. They killed us not only in a physical way. When we think of who we are and what is shaping our identity, it is our history, our language, our dances, our food, our legends, our art, and our ethics. To erase this is to erase who we are, our identity. This also amounts to killing us. That is why for us, the nation-states that have been imposed from outside mean death. After 100 years we absolutely need another solution, a non-state one. In the revolution in North and East Syria, we are building up a stateless democracy that is a concrete alternative to the nation-state.

Today, the peoples of North and East Syria are practicing a peace solution, so much so that the relative tranquility of the territories under control of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria is attracting populations fleeing from other parts of Syria. In recent months, the Autonomous Administration has made a concrete 9-point proposal for a democratic Syria, a concrete proposal to resolve the crisis with the peoples’ voice. In spite of this, the so-called peace talks that are held in Geneva under the auspices of the UN as well as the ones in Astana (Kazakhstan) with the participation of Russia, Iran, Turkey and Syria, do not include the participation of the people living in the areas of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria. In this way, they lack the perspectives of the people practicing concrete peace solutions on the ground.

These concrete peace solutions refer to the model of the democratic nation described by Abdullah Ocalan. A nation in which all nationalities can find their place and express their colors. A nation that can organize from below to meet its needs. A nation that does not become a state. A nation that would place women’s liberation at its center and through this build up an ecological, democratic society based on people’s ethics and capacity for self-determination. A revolution is occurring not only in the way of organizational practices, but also in the way of understanding life. A revolution that takes its roots from the roots of humanity, referencing the time when there were not yet emperors, no gender oppression, and no exploitation of nature. A revolution that includes within its path the fight of the Kurdish people and the fights of all the oppressed people in the world. A revolution that is taking place here in North and East Syria and that we as YPJ are proud to defend. A practical experience that is a promise for the world. This is what we are doing 100 years after Lausanne.

Today the powers claim to solve the crisis that we are experiencing with the use of instruments of death such as nation-states. In this situation, the democratic nation becomes not only a proposal but becomes a promise of life for Kurdistan, the Middle East and ultimately for the world. In the words of Berivan Xaled, co-chair of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, “Today we, the victims of the Treaty of Lausanne, promise to defend the achievements of this revolution and to make the democratic nation project an international project.”